Finding hope from conflicting data.

When my husband started drinking diet sodas and using artificial sweeteners (AS) in his coffee, his weight went up. I didn’t think much of it until I attended a Continuing Medical Education (CME) conference for physicians last month on diabetes. There I asked the two endocrinologists who were giving the speech if they knew about a relationship between artificial sweeteners, weight gain, and diabetes. They answered that more studies needed to be done on that subject but that they noted that most of their patients gained weight after they started using artificial sweeteners. This puzzled me.

I decided to dive into 10 years worth of medical literature and research and found intriguing facts:

Intriguing research:

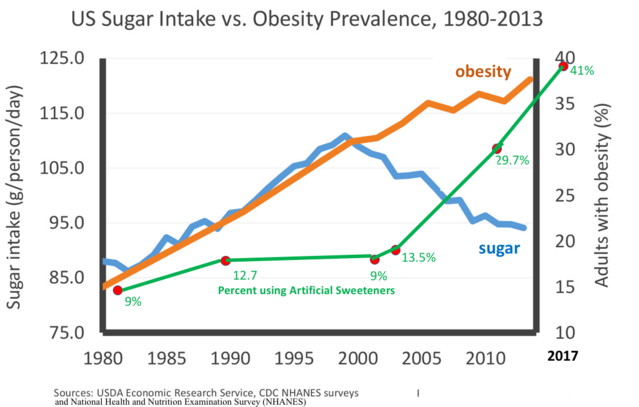

I found that indeed when people start using artificial sweeteners they don’t lose weight. In fact, when we look at data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination survey and from the USDA economic research service (see the fig. below), we see that from 1980 to about 2000, obesity increased in the USA in correlation with sugar intake but that, since 2000, sugar intake is steadily decreasing and non-caloric artificial sweeteners are increasing every year and yet, the percentage of obese people is continuing to increase at the same rate despite replacing a lot of nutritive sugars by non-nutritive artificial sweeteners.

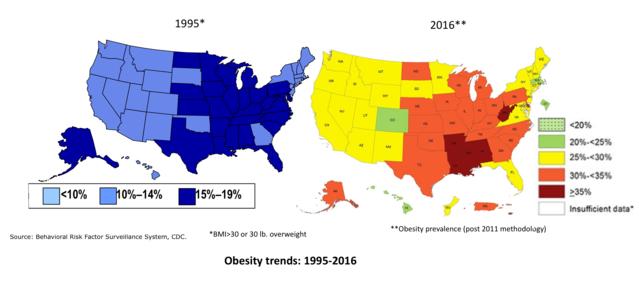

As far as obesity goes, you see that in 1995, no state had over 19 percent of the population with obesity whereas, in 2016, most of the USA has over 25 percent of the population that is obese.

Yet, there is a controversy because several studies show that artificial sweeteners do not increase pancreatic enzyme secretion (insulin or glucagon) nor hunger. But what is puzzling is that other studies show that the more obese people become, the more artificial sweeteners they use indicating a positive dose-response relationship between AS consumption and long-term weight gain.

The Growing Up Today Study, involving 11,654 children aged 9 to 14 reported positive association between diet soda and weight gain for boys.

S. Fowler at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio demonstrated that consuming more than 21 artificially sweetened beverages per week versus none doubled the risk of being overweight among 1,250 individuals with baseline normal weight over 9 years.

Allison C. Sylvetsky and colleagues reported in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics this year found that 25.1 percent of children and 41.4 percent of adults consumed low-calorie sweeteners in the USA and that the frequency of consumption increased with body weight in adults.

So we see that obesity and use of artificial sweeteners are correlated but correlation doesn’t mean causation. Yet one thing is for sure: artificial sweeteners don’t make people lose weight. Why is that? And why are people continuing to gain weight despite consuming more artificial sweeteners?

The explanation could be in the last few years of research studies:

A possible answer:

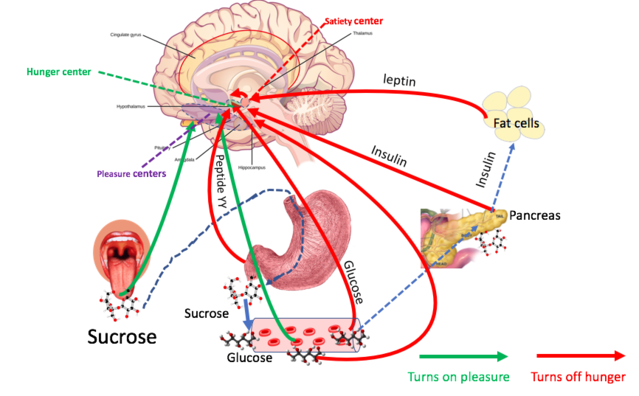

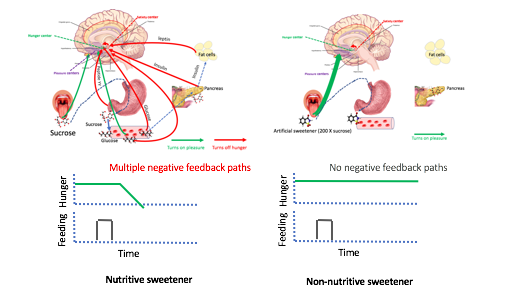

When we ingest regular sugar, the sweet taste receptors in our tongue are activated at the same time as calories get in our blood (see images below). This sweet taste activation sends signals to our brain, especially the thalamus then to our amygdala, anterior insula, and orbitofrontal cortex, creating secretion of dopamine and serotonin and giving us the sensation of pleasure. At the same time, the calories getting into our blood stimulate our hypothalamus which sends signals back to the hunger center, turning off hunger signals because our bodies have enough calories for our energy needs. There are several more organs that turn off hunger signals: our ileum and colon via Peptide YY secretion, our pancreas via insulin secretion and our fat cells via leptin secretion when they received enough calories.

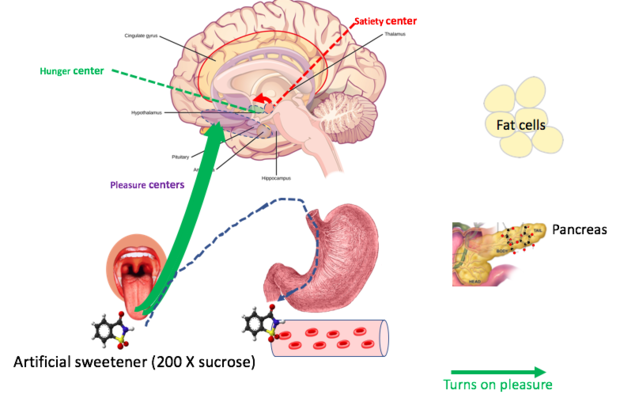

By contrast, when we ingest artificial sweeteners, the sweet taste receptors in our tongue are activated but at the same time, no calories get into our blood. This sweet taste activation sends signals to our brain giving sensations of pleasure. But the hypothalamus doesn’t get stimulated so no feedback is sent to hunger centers indicating that we can now stop ingesting food. Our ileum, colon, pancreas, and fat cells don’t get any calories either so the consequence is that we continue ingesting artificial sweeteners because our body still needs calories.

Let’s look at the feedback loops more closely comparing nutritive sweeteners (sucrose, also known as table sugar, for example) and non-nutritive artificial or natural sweeteners:

With nutritive sugars (using sucrose for example) we have a lot of pleasure and also lots of signals that turn off hunger.

With non-nutritive artificial sweeteners, there is an intense pleasure but no signal that will turn off hunger (because there are no calories ingested).

This could be okay if artificial sweeteners were as sweet as sugar but they are not. They give a sweet flavor that is 200 (aspartame) to 600 to 700 (sucralose) to 20,000 (advantame) times more potent than regular sugar, as a consequence, our mouth gets used to very strong sweet tastes. As we consume more and more AS, our mouth gets used to sweeter and sweeter tastes. This is a phenomenon called adaptation which means that the sweeter and more frequent sweet ingestion we have, the less sensitive our tongue and our brain become to those sweet tastes. We need more and more sweetness to get the same pleasure. Addiction to sweeter tastes starts.

The biggest problem comes when we eat a lot of processed foods (cereal, bread, cakes, cookies, donuts, etc.) which contain a lot of regular sugar. In order to taste good, they need to match the sweetness of the AS, so a huge amount of regular sugar is needed to satisfy our taste buds, thus a huge amount of calories.

Studies done by Jacquelyn Szajer and colleagues and published in 2017 in Brain Research used fMRI to compare the brain activation for obese people and non-obese people with the same amount of regular sugar (sucrose). They found that there was significantly less activation of the left amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex (responsible for pleasure) in the group of obese people.

So, we can deduce from all the above studies that chronic AS overstimulation of sweet receptors on the tongue leads to the need for more sweetness in processed foods to match the sweetness of soft diet drinks and food with AS. This could be one of the reasons why people gain weight. Not only do they end up eating more calories but they also end up eating higher glycemic index foods, such as bread and pasta, which leads to secretion of insulin which stores calories in fatty tissues, increasing the person’s fat and weight.

Also, chronic elevated secretion of insulin leads to a type of sensory adaptation called insulin resistance (cells don’t respond to insulin as much) causing the pancreas, which secretes insulin, to get overworked pumping out ever greater levels of insulin, and to eventually burn out, producing diabetes.

Novel diet ideas:

Based on the above hypothesis, it seems it would be great to find a sugar that brings the lowest glycemic index/sweetness ratio possible while still bringing in calories capable of turning off the brain’s hunger centers.

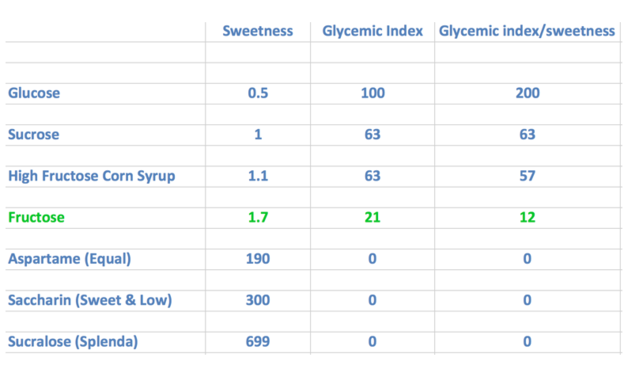

Let’s compare sweetness, glycemic index, and glycemic index/sweetness ratio of different sweeteners:

Looking at the chart above, the sugar that has the lowest glycemic index/sweetness ratio above zero is fructose (which is 1.7 times sweeter than sucrose and yet, has a low glycemic index). Indeed, fructose is available to buy online and can be used for cooking and baking. The feedback loop concepts discussed earlier suggest that fructose might—and I emphasize might—represent a happy medium between consuming sweeteners with too low and too high a glycemic index, because fructose has a low glycemic index, but, unlike AS, is metabolized into glucose which eventually turns off hunger in the brain.

Magdalena Madero and colleagues, writing in the journal Metabolism in 2011, report that natural fructose diets do indeed hold promise for promoting weight loss, but much more research is required before consuming fructose sweeteners is shown to be safe and effective in weight control.

On the other hand, some people really want to keep drinking diet sodas and using artificial sweeteners in their coffee or tea. For those individuals, the solution could be to drink a mixture of sparkling water and diet soda, finding the least amount of diet soda needed for the sparkling water to taste good. As for artificial sweeteners in coffee, they could try to instead of using the whole pack of AS, using half a pack or a third of it. They will find that they really don’t need to use the whole pack for their coffee or tea to taste good.

For those people, baking their own cookies and cakes would make sense using AS but they need to remember that AS are at a minimum 200 times sweeter than sugar so the key is to bake with as little AS as needed to give a pleasurable feeling on the tongue. The problem will be to convince commercial bakeries to do the same thing in order to avoid the addiction and adaptation to sweet taste.

In summary, new research exploring the paradoxical connection of AS to weight gain suggests—but does not yet prove—a few simple weight loss ideas: mix sparkling water with your diet soda and use as small quantities of fructose or artificial sweeteners as possible in your coffee or tea, and for cooking and baking in order to avoid adaptation and addiction.

Life is sweet but could be even sweeter if we ingest less sweetness.

Haase L, Cerf-Ducastel B, Murphy C. Cortical activation in response to pure taste stimuli during the physiological states of hunger and satiety. NeuroImage. 2009;44:1008–1021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] 53 50 to 53

National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence of overweight, obesity and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960-62 through 2005-2006. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Ankur Vyas, Linda Rubenstein, Jennifer Robinson, Rebecca A. Seguin, Mara Z. Vitolins, Rasa Kazlauskaite, James M. Shikany, Karen C. Johnson, Linda Snetselaar, Robert Wallace, Diet Drink Consumption and the Risk of Cardiovascular Events: A Report from the Women’s Health Initiative, Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2015, 30, 4, 462

Soffritti MBF, Tibaldi E, Esposti D, Lauriola M. Life-span exposure to low doses of aspartame beginning during prenatal life increases cancer effects in rats. Environ Health Perspect 2007; 115: 1293–1297.

Szimonetta Lohner, Ingrid Toews, Joerg J. Meerpohl, Health outcomes of non-nutritive sweeteners: analysis of the research landscape, Nutrition Journal, 2017

Jacquelyn Szajer, Aaron Jacobson, Erin Green, Claire Murphy, Reduced brain response to a sweet taste in Hispanic young adults, Brain Research, 2017, 1674, 101

D. Ruanpeng, C. Thongprayoon, W. Cheungpasitporn, T. Harindhanavudhi, Sugar and artificially sweetened beverages linked to obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis, QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 2017, 110, 8, 513

Monika Saltiel, Rune Kuhre, Charlotte Christiansen, Rasmus Eliasen, Kilian Conde-Frieboes, Mette Rosenkilde, Jens Holst, Sweet Taste Receptor Activation in the Gut Is of Limited Importance for Glucose-Stimulated GLP-1 and GIP Secretion, Nutrients, 2017, 9, 4, 418

Yilin Qu, Rongyan Li, Mingshan Jiang, Xiuhong Wang, Sucralose Increases Antimicrobial Resistance and Stimulates Recovery of Escherichia coli Mutants, Current Microbiology, 2017, 74, 7, 885

Allison C. Sylvetsky, Yichen Jin, Elena J. Clark, Jean A. Welsh, Kristina I. Rother, Sameera A. Talegawkar, Consumption of Low-Calorie Sweeteners among Children and Adults in the United States, Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2017, 117, 3, 441

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3856475/#R3

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3220878/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3772345/

http://chemistry.elmhurst.edu/vchembook/549sweet.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/2758952/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3982014/table/Tab2/

http://www.sugar-and-sweetener-guide.com/glycemic-index-for-sweeteners…